A Bridge Between Two Worlds

The gap between a high school student today and a student from forty years ago is wider than almost any other generational divide in history. When we talk to our grandkids about our teenage years, we aren't just talking about different fashion or music; we are describing a world that functioned on entirely different physical laws. To a teenager in 2026, the idea of being "unreachable" or having to wait a week to see a photograph feels like a strange myth. Our high school experience was defined by physical objects, manual effort, and a specific type of social privacy that has completely vanished. Sharing these stories isn't just about nostalgia; it is about helping the younger generation understand how much the human experience has changed in a very short time. Here are the things from our school days that leave our grandkids truly puzzled.

Passing Physical Notes in Class

Before teenagers could hide their phones under their desks to text, we had to communicate using the "physical note." This involved writing on a piece of notebook paper, folding it into an elaborate geometric shape, and carefully passing it from person to person when the teacher wasn't looking. There was a huge risk involved; if the teacher caught the note, they might read your most private secrets out loud to the entire class. Our grandkids find this incredibly primitive. They can send a disappearing message or an encrypted text to a group of ten people instantly without moving a muscle. They don't understand the tactile thrill of receiving a folded piece of paper or the skill it took to pass a message across a room without ever making eye contact.

The Social Stress of the Landline Phone

In our high school years, the telephone was a heavy object attached to a wall, usually in the middle of the kitchen or a hallway. If you wanted to call a crush or a friend, you had to dial their home number and potentially speak to their father or mother first. There was no caller ID to warn them who was calling, and there was no privacy unless you had a cord long enough to stretch into a closet. Our grandkids, who have had personal smartphones since middle school, cannot imagine the bravery it took to navigate the "parent filter" just to ask about homework. The idea that a single phone line served an entire family and could be "busy" for hours is a concept that feels completely ancient to a generation that lives on instant, individual digital connections.

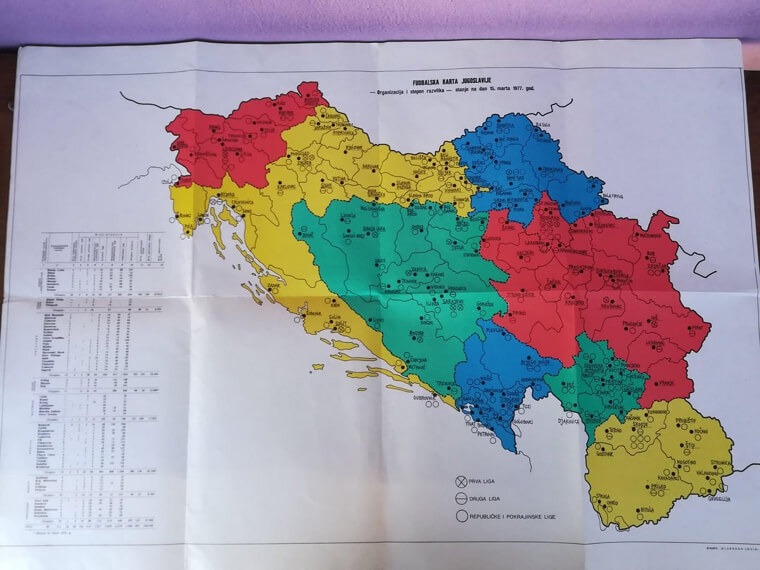

Using a Paper Map to Get Anywhere

Before GPS lived in everyone's pocket, high schoolers had to master the art of the paper map. If you were driving to a party in an unfamiliar neighborhood or heading to an away game, you had to unfold a giant sheet of paper that never quite folded back the right way. You had to memorize turns or have a friend in the passenger seat shouting directions while trying to read street signs in the dark. Our grandkids find it hilarious that we couldn't just "see" where we were on a screen with a blue dot. They don't understand the feeling of being genuinely lost or having to pull over at a gas station to ask a stranger for help. For us, navigation was a skill you had to learn; for them, it is a utility that is simply always there, like running water or electricity.

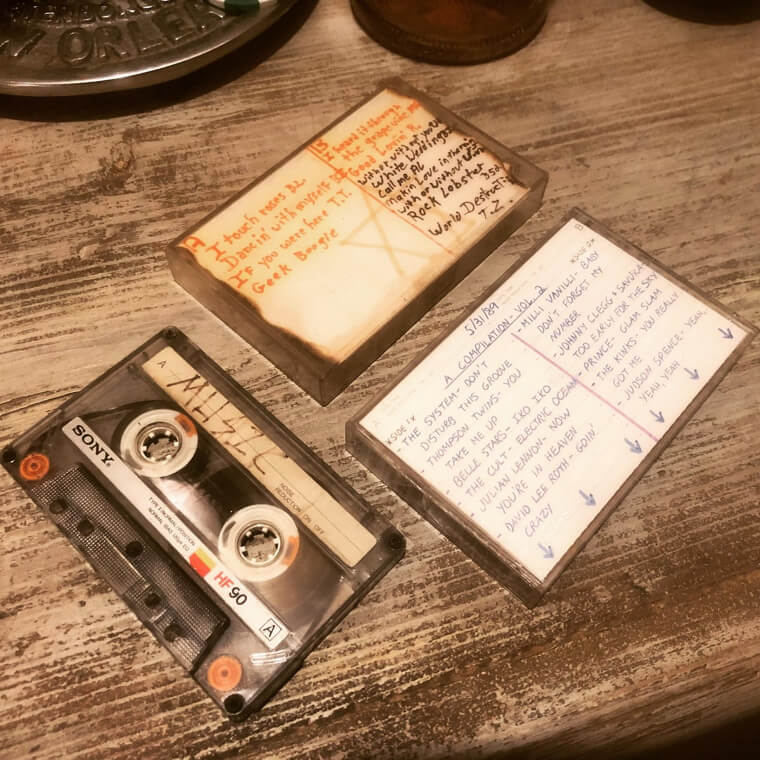

The Ritual of the Mix Tape

Today, sharing music is as simple as sending a link to a playlist that contains millions of songs. In high school, showing someone you cared about them involved the labor-intensive process of making a mix tape. We had to sit by the radio for hours, waiting for a specific song to play so we could hit the "record" and "play" buttons at exactly the right moment. We had to pray the DJ didn't talk over the intro or the ending. Writing out the tracklist by hand on the little paper insert was a final touch of personalization. Our grandkids see music as a boundless, free resource, but for us, a mix tape was a physical gift of time and effort. They struggle to understand why we would spend a whole afternoon creating something that only held forty-five minutes of music.

Researching With a Printed Encyclopedia

When we had a term paper due, we couldn't just type a question into a search engine and get a million answers in half a second. We had to go to the library and use the Dewey Decimal System to find a physical book. If the library was closed, we relied on the set of encyclopedias our parents kept on the bookshelf, which were often five or ten years out of date. We had to flip through heavy volumes, look for keywords, and take notes by hand. Our grandkids live in a world of "instant facts," where every piece of human knowledge is accessible from a watch or a phone. The idea that information was once "stuck" inside physical books that you had to travel to find is one of the hardest things for them to wrap their young minds around in 2026.

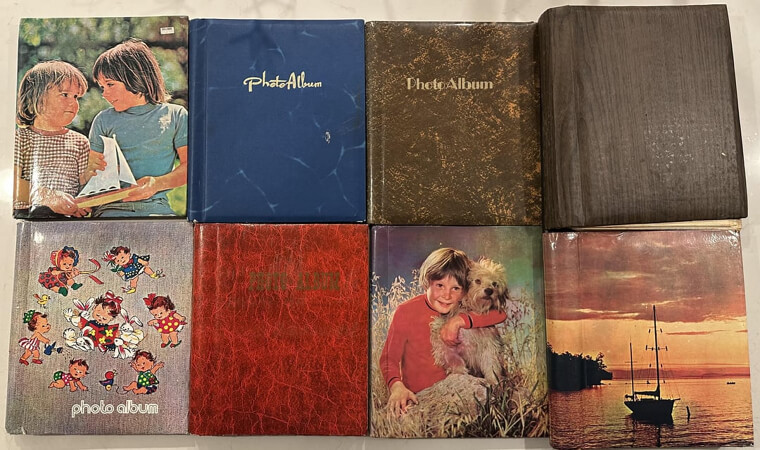

Waiting for Photos to Be Developed

In high school, we took pictures with cameras that used actual rolls of film. You only had 24 or 36 chances to get the perfect shot, so you didn't waste them on pictures of your lunch. The most confusing part for our grandkids is that we didn't know if the photos were any good until a week later. We had to take the film to a pharmacy or a "photo hut," pay money, and wait for them to be chemically processed. Opening that envelope was a moment of high drama; you might find out your finger was over the lens or that everyone’s eyes were closed. The concept of "instant feedback" or taking 500 selfies to find one good one didn't exist. We lived with the mystery of our memories, and those physical prints were rare and precious items we kept in shoeboxes.

Being "Out of Pocket" and Unreachable

There was a specific kind of freedom in our high school years that came from the fact that once you left your house, no one could find you. If you were at the mall or the park, your parents simply had to trust that you would be home by your curfew. There were no tracking apps, no "read receipts," and no constant pings of text messages. Our grandkids are used to being digitally tethered to their parents and friends 24 hours a day. They often feel anxious if they don't get a reply to a message within minutes. They find the idea of being "unreachable" for an entire afternoon to be terrifying rather than liberating. Explaining that we spent our teenage years in a state of total digital silence is like describing a world without oxygen to them; they don't know how we survived.

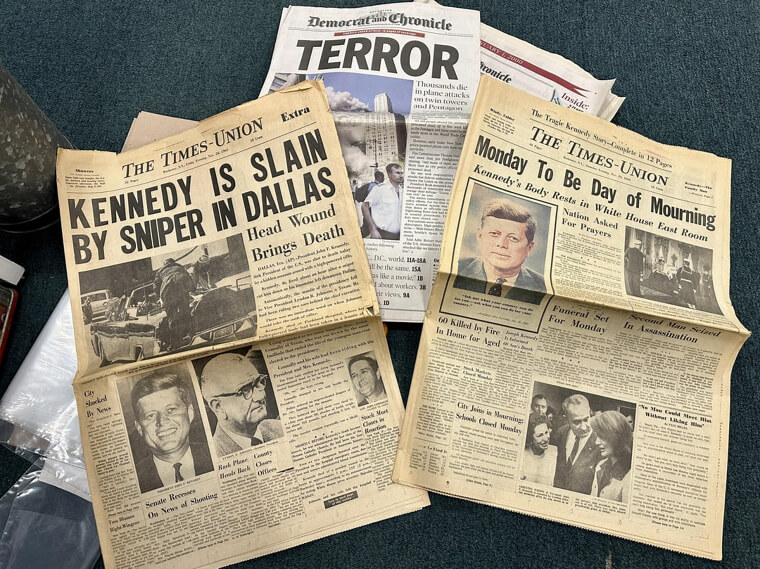

Looking Up Showtimes in a Newspaper

If we wanted to go to the movies on a Friday night, we didn't check an app. We had to find the local newspaper, turn to the entertainment section, and look at a tiny grid of text to see when the film started. If we missed the start time, we had to wait two or three hours for the next showing, or we just walked into the theater halfway through and watched the ending first. Our grandkids are used to "on-demand" everything. They can watch any movie ever made at any time they want. The idea that we were at the mercy of a printed schedule and a physical building seems like a massive inconvenience to them. They don't understand the communal experience of everyone in town looking at the same paper to decide where they were going to be that night.

The Meaning of a "Busy Signal"

One of the most frustrating sounds of our youth was the "busy signal"-that rapid, rhythmic beeping that meant the person you were calling was already on the phone with someone else. You couldn't leave a voicemail, and there was no "call waiting" to let them know you were trying to get through. You just had to hang up and try again every ten minutes. Our grandkids have never heard this sound. To them, a phone is a computer that handles multiple streams of data at once. They don't understand the concept of a "blocked" line or the patience required to wait for a friend to finish a conversation with their grandmother so you could finally talk. It was a lesson in patience and persistence that has been completely erased by the era of modern, multi-tasking communication technology.

Manual Window Cranks and Car Keys

When we got our first cars in high school, they were purely mechanical machines. To lower the window, you had to physically turn a plastic crank on the door. To start the engine, you had to put a metal key into a slot and turn it. There were no buttons to push and no proximity sensors. If you forgot your keys inside, you were locked out, and there was no app to unlock the doors remotely. Our grandkids, who are used to cars that recognize their phones and have touchscreens for every function, look at these old manual controls like they are museum artifacts. They find it exhausting to imagine having to "work" just to get a breeze or start the car. To us, these were just the standard tools of the road, but to them, they are symbols of a much more difficult, hands-on era.