Local Meals

Fast food existed in 1975, but it hadn't taken over the roadside yet. Pulling off the highway for lunch still meant looking for a diner or a local cafe, parking in a gravel lot, and walking into a place with vinyl booths, laminated menus, and a waitress who called everyone hon without thinking about it. The food was straightforward - grilled cheese, burgers, pie under a glass dome on the counter. It tasted different at every place you stopped, because every place actually made it differently. If you behaved yourself through the first half of the drive, there was a chance a milkshake was coming. You didn't linger too long, but you didn't rush either. Somewhere out there is a diner you stopped at once in 1975 whose name you never knew, and you can still picture the booth you sat in.

No Boredom, Just Car Games

No screens, no headphones, no way to disappear into your own world for the next four hours. If you were bored, fixing it was entirely your problem. I Spy could stretch on for a surprisingly long time if everyone played honestly. The license plate game turned every passing car into a small victory. Counting cows was taken seriously, and losing your count when someone yelled "cemetery" felt like a genuine setback. You stared out the window and invented whole lives for the people in cars going the other direction. Sometimes you sang along to the radio. Sometimes you fought over nothing. But you were never really checked out - your eyes were on the road, the fields, the billboards, and whatever was coming next. That kind of boredom made you pay attention to the world going by.

Gas Stops Like Clockwork

The cars of 1975 were not fuel-efficient, and nobody pretended otherwise. The gauge moved visibly on long drives, and pulling off for gas happened on a reliable schedule whether you planned for it or not. A gas stop wasn't something to rush through - it was a natural break in the trip. You got out and stretched. Dad talked to the attendant, who actually came out to pump the gas, check the oil, and clean the windshield without being asked. Mom organized whatever had shifted in the back seat. You went inside to use the bathroom and came back with something from the vending machine if you were lucky. The whole operation could take five minutes or thirty, depending on how the conversation went. Nobody was impatient about it. Stopping was just part of how a long drive worked.

Static and Songs

Every time dad reached for the AM radio dial, it was a gamble. You didn't choose your playlist - you got whatever the airwaves decided to give you that day. Sometimes it came in crystal clear and filled the whole car. Other times it sounded like the DJ was broadcasting from inside a tin can at the bottom of a lake. When the signal faded out entirely somewhere between towns, you just sat there and waited, hoping it drifted back. The highlight of any long drive was catching the weekly countdown show - even songs you didn't like felt worth listening to when they were ranked and announced with that kind of ceremony. That crackle and hiss became part of what a road trip sounded like, and honestly, it still does in your memory.

The Giant Map

Dad had a road map, and that map was enormous. Unfolding the whole thing meant it immediately took over the front seat - blocking part of the windshield, draped across the steering wheel, spilling onto Mom's lap. It never folded back the same way twice, which meant it spent most of the trip in a crumpled state that made finding anything on it twice as hard. If you were in the back seat and got recruited to help navigate, you held your section up to the window trying to match the tiny print to whatever was flying past outside. Missing an exit meant a family discussion that could last thirty miles. Getting genuinely lost meant an adventure nobody had planned for. You didn't always know where you were, but you always figured it out eventually.

8-Track Memories

If your family's car had an 8-track player, you felt the difference immediately. Those chunky tapes slid into the slot with a satisfying click that felt mechanical and solid in a way nothing does anymore. You had your favorites ready before you even left the driveway. The catch - and there was always a catch - was that the tape switched tracks whenever it felt like it, which was usually right in the middle of the best song on the whole tape. You couldn't skip ahead, couldn't rewind, couldn't do anything except wait for it to come back around. When the tape jammed, Dad pulled it halfway out and fiddled with it while driving, which felt dangerous and somehow worked. Those tapes got played until they wore out, and you knew every word of every song on all of them.

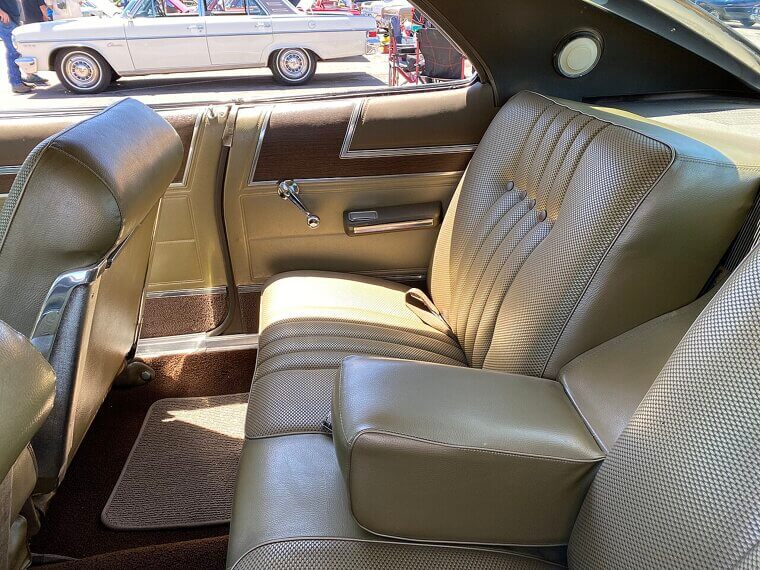

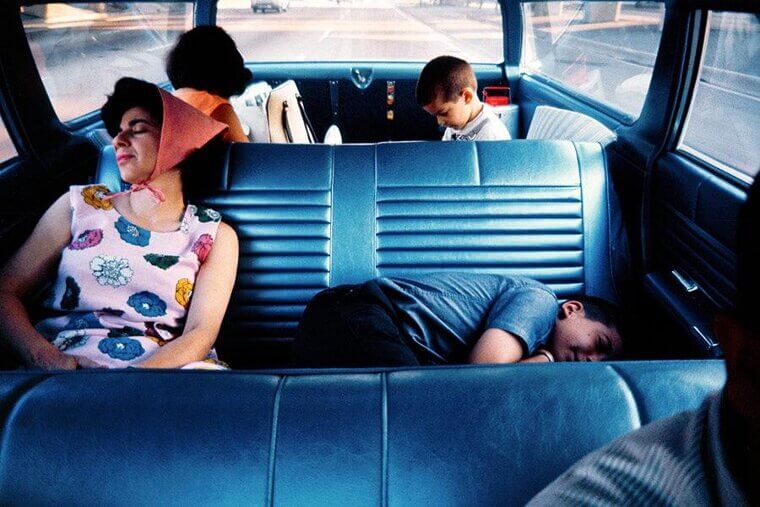

Bench Seat Memories

The back seat of a 1970s family car wasn't really a seat - it was more like a couch that happened to be moving at sixty miles per hour. No buckets, no center console, no dividers of any kind. You slid from one side to the other on every curve, piled on top of siblings during long stretches, and stretched out completely flat when you needed a nap with your head in someone's lap and your feet up on the window. Seatbelts, if the car had them in the back at all, were mostly decorative. Nobody thought much about it. The bench seat meant the back of the car belonged to the kids, and the kids used every inch of it. It wasn't safe by any modern measure, but it felt like freedom, and that's the part that stayed with you.

The Backward Secret Seat

Station wagons had a rear-facing seat in the very back, and if you were lucky enough to claim it, you already knew you'd won the day. Everything about it felt different back there. You faced the wrong direction, watched the road disappear behind you instead of coming toward you, and felt slightly separated from whatever was happening in the rest of the car. You waved at drivers behind you and waited to see who waved back. You watched towns shrink away instead of approaching. Time moved differently from that seat - slower and more interesting. It wasn't comfortable exactly, and there was nothing to hold onto when the car turned hard, but none of that mattered. Kids fought for that seat at the start of every trip, and the one who got it felt like they'd gotten away with something.

Seats That Tried to Cook You

You knew it was going to be a long day the moment you opened the car door and the heat came rolling out. Vinyl seats in the 1970s absorbed every bit of summer sun and held onto it like a weapon. The backs of your legs made contact and you felt it immediately. Shorts were optimistic. Mom put towels down before anyone got in, which helped for about the first ten minutes until the towels heated up too. The car had air conditioning, maybe, or it had a broken air conditioner that blew warm air while making a noise like it was trying. Either way, the windows came down and stayed down. Your hair went in every direction. The smell of hot vinyl and road dust and whatever snacks were in the bag mixed together into something that still brings the whole memory back.

Ashtrays Everywhere

Every car in the 1970s came with ashtrays built right in - front doors, back doors, dashboard - regardless of whether anyone in your family smoked. They were as standard as the steering wheel, just part of what a car interior looked like. The cigarette lighter lived in its little socket on the dashboard, and parents told kids not to touch it, which had roughly zero effect. Everybody touched it at least once, just to see the orange glow when it popped out. If nobody in your family smoked, the ashtrays collected loose change, receipts, and whatever small objects needed somewhere to go. They were always full of something. It feels like a different world now, and it was - a world where nobody questioned why every car needed four separate places to put out a cigarette.

Polaroids and Memories

The camera came out at the important moments - the overlook with the view, the sign at the state line, everyone squinting into the sun in front of something worth remembering. If it was a Polaroid, you watched the photo develop in your hand, waving it gently the way everyone did even though you weren't sure it actually helped. The image came up slowly, colors bleeding in from the edges until the whole thing was there. They weren't sharp. The lighting was usually wrong. Someone was always mid-blink. But they were real in a way that felt different from any photo you take today - unedited, unfiltered, and impossible to retake. Those pictures ended up tucked into shoeboxes and desk drawers, faded to soft colors over the decades, still exactly what that moment looked like on that particular afternoon.

Souvenirs

Every stop had a gift shop, and every gift shop had the same things in slightly different versions. Pennants in the local colors with the town name in big letters. Postcards you picked based on which photo looked most like what you actually saw. Keychains, snow globes, small ceramic figures of landmarks you'd just driven past. You didn't buy much - budgets were real - but you always came away with something. Those objects ended up tacked to bedroom walls, lined up on shelves, or buried in a shoebox that surfaced years later during a move. Each one was a physical record of a place you'd been, something you could hold and point to. You can still picture where you bought half of them, which gas station or roadside stand, which dusty shelf it came off of.

Backseat Border Wars

At some point on every long drive, someone crossed the line. It was invisible, this line - never formally established, always completely understood - and crossing it was grounds for immediate escalation. You had your side and your sibling had theirs, and the space in between was contested territory that shifted with every curve in the road. Elbows were deployed as weapons. Complaints were filed loudly with the front seat. Dad said something without turning around. Mom said something more specific. Neither had any lasting effect. You built walls out of pillows and jackets that held for about twenty minutes. The fights felt enormous in the moment and ridiculous the moment they ended, which was usually when something interesting appeared outside the window and everyone forgot what the argument was about. No road trip was complete without at least one of them.

Windows Down

The air conditioning in a 1970s family car was often not working, or working in a way that made things worse. When it gave out somewhere in the middle of August, the windows came down and stayed down. At highway speed the noise was significant - conversation required real effort, and the radio was mostly lost to the wind. Your arm went out the window and you found the angle where it could float on the airflow, fingers spread, hand rising and falling with small adjustments. Your hair went completely sideways. Anything loose in the car became a flight risk. At slower speeds the heat came right back in, which meant the only solution was going faster, which Dad was generally willing to do. The combination of noise and heat and wind made you feel like you were actually moving through the world rather than just riding through it.

Are We There Yet?

The question came up reliably about forty-five minutes into any drive that was supposed to take more than an hour. You measured progress by landmarks, by the number of billboards for the same attraction, by how many snacks were left in the bag, by the angle of the sun. The miles between here and there felt enormous when you were ten years old with nothing to do but watch the distance not close fast enough. Dad gave updates in terms that weren't always helpful. You went back to the window and watched the country go by. And then, eventually, there was the exit, the familiar turn, the sign that meant you were almost there. Everything that had been long and slow and slightly too hot suddenly collapsed into arrival. You'd made it. The drive already belonged to the past, and somehow it was already the part of the trip you'd remember.