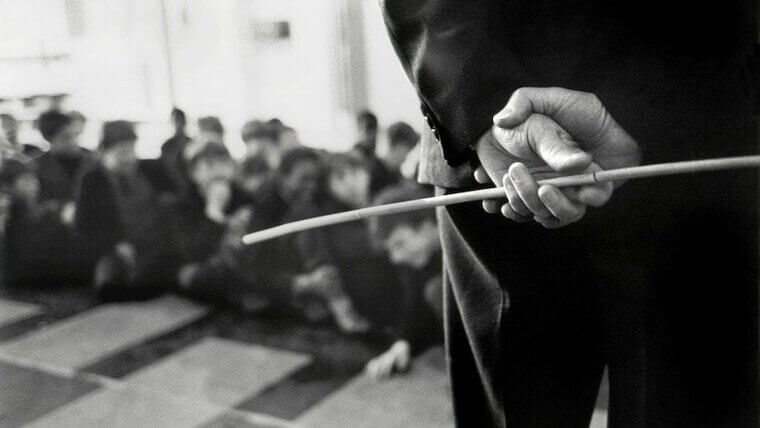

Corporal Punishment

If you went to school in the 1980s, there's a good chance you knew exactly what getting sent to the principal's office really meant. Paddling was a routine disciplinary tool in schools across most of the country - a wooden paddle kept in the office and used on students who stepped out of line. Parents knew about it, and most didn't object. The thinking was straightforward: the fear of physical punishment kept kids in line better than a detention slip ever would. Whether it actually worked that way is another matter. Most states have since banned corporal punishment in public schools, and the research on its lasting psychological effects changed how educators think about discipline entirely. For those who experienced it, the memory tends to stick around long after the sting faded.

School Buses Lacked Seat Belts

You rode to school every day in a vehicle with no seat belts and probably never thought twice about it. School buses in the 1980s didn't have them, and the federal government didn't require them. The reasoning offered at the time centered on something called compartmentalization - the idea that high, padded seat backs placed closely together would absorb the impact of a collision well enough to protect passengers without restraints. Whether most parents found that convincing is another question. The debate over seat belts on school buses has continued for decades, with some states now requiring them and others still relying on that same compartmentalization argument. It's one of those things that felt normal at the time simply because everyone did it the same way.

Dodgeball With No Mercy Rules

Remember lining up in the gym while the PE teacher divided everyone into two teams and rolled out those hard rubber balls? Dodgeball in the 1980s was a full-contact elimination game with one simple rule - don't get hit. There were no soft foam balls, no restrictions on how hard you could throw, and no teacher stepping in when a kid was clearly being targeted by the bigger boys. If you were small, slow, or just unlucky, you spent most of gym class standing against the wall watching everyone else play. Schools today have largely eliminated or heavily modified dodgeball because of the physical risk and the way it allowed stronger kids to single out weaker ones. At the time, though, it was just Tuesday.

No Anti-Bullying Policies

If you were bullied in the 1980s, the advice you got was probably some version of toughing it out. Schools had no formal anti-bullying policies, no reporting structures, and no real framework for taking it seriously as an institutional problem. The prevailing attitude among adults was that kids sorting out social hierarchies was a normal part of growing up - uncomfortable, maybe, but not something that required intervention. What's become clear since then is how wrong that assumption was. Adults who experienced serious bullying in the 1980s have been vocal about the lasting effects it had, and the research has backed them up. Schools today operate under comprehensive policies that cover physical, verbal, emotional, and online harassment. The shift didn't happen overnight, but it happened - and for good reason.

Typing Class on Manual Typewriters

If you took typing class in the early 1980s, you remember the sound - rows of students hammering away on manual typewriters, the carriage return bell ringing every few seconds across the room. Learning to type was considered a practical life skill, mostly aimed at girls who might become secretaries. The idea that every student would eventually need a computer was still years away from becoming school policy. Meanwhile, Apple had already introduced the personal computer, and the digital revolution was quietly beginning outside the classroom walls. By the time many 1980s students graduated, the typewriter was already becoming obsolete. Looking back, it's striking how close schools came to sending an entire generation into a computerized world with no preparation for it whatsoever.

Searching Lockers and Bags

If a teacher or principal in the 1980s decided they wanted to look through your locker or your bag, they generally just did it. The guiding legal doctrine was in loco parentis - Latin for "in the place of a parent" - which gave school officials broad authority to act as parents would, including searching students' belongings without a warrant, without a police officer present, and without what courts would consider probable cause. Students had little recourse. Today the standards are more defined - school officials need reasonable suspicion before conducting a search and are expected to be able to justify it. Lockers are often still considered school property, which complicates the privacy question, but a student's personal bag carries significantly stronger protections than it did forty years ago.

Mental Health Support Was Almost Nonexistent

Your guidance counselor in the 1980s was a good person to know when it was time to pick classes or request a college recommendation letter. For anything beyond that, you were mostly on your own. The role of school counselors as mental health support was barely defined, and most had no training in recognizing or responding to students who were struggling emotionally. A student dealing with anxiety, depression, a difficult home situation, or the ordinary turbulence of adolescence had few formal options for support within the school building. Today, school counselors are trained to identify and respond to a wide range of student wellbeing concerns, and schools operate under federal guidelines that require appropriate responses. The evolution of that role over the past four decades reflects how much the understanding of student wellbeing has changed.

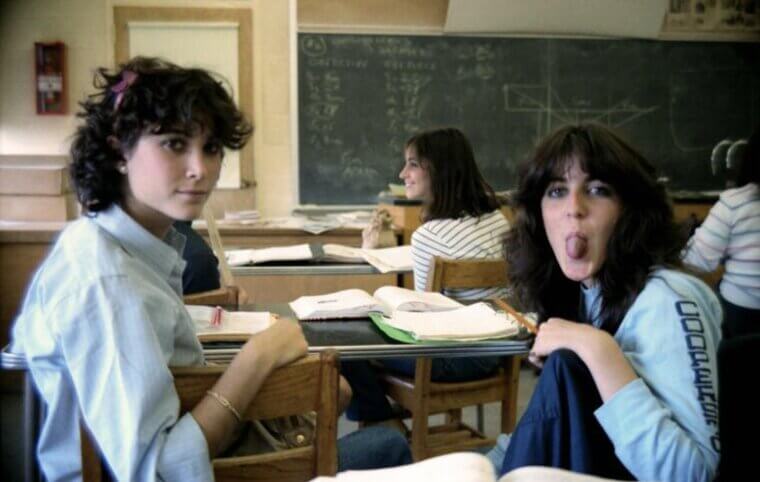

Open Campus With No Sign-Out Rules

Lunch period in the 1980s meant something very different than it does today. If your school had an open campus policy - and many did - you could walk off school grounds, drive to a fast food restaurant, and come back whenever you felt like it. No sign-out sheet, no parent permission slip, no attendance check at the door. Some students stretched lunch into the better part of an afternoon without anyone raising an alarm until the next morning. Schools today operate almost entirely as closed campuses, with strict rules about leaving during the school day and consequences for students who do. The shift happened gradually as liability concerns and safety awareness grew. But for a few years in the 1980s, lunch could feel remarkably like freedom.

No Background Checks on Teachers

Hiring a teacher in the 1980s was a much simpler process than it is today - and not in a good way. Schools relied on credentials, interviews, and phone calls to previous employers. There was no national database, no standardized criminal history search, and no reliable way to find out whether someone applying at your district had been quietly let go from another one for misconduct. A teacher with a serious problem in their past could move to a new town and walk into a new classroom without anyone finding out. Today, comprehensive background checks are mandatory in all fifty states before a teacher can be hired. It closed a gap that most families at the time didn't know existed, and probably didn't want to think about.

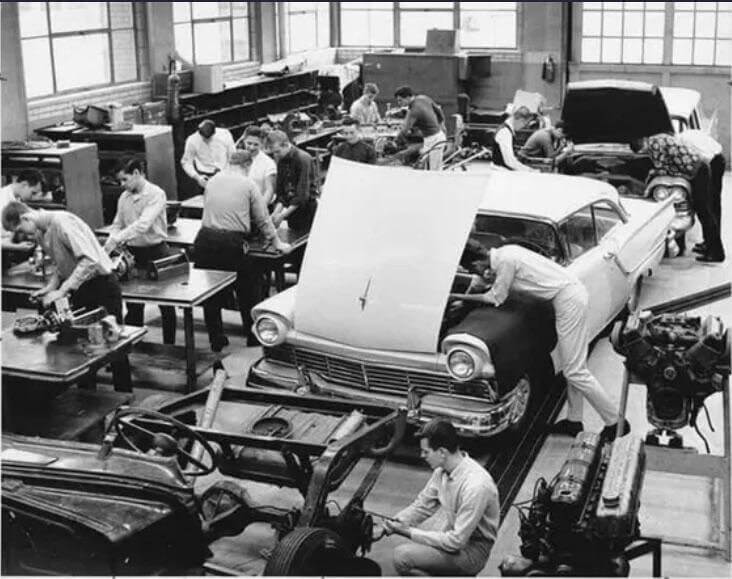

Unsupervised Classes

Shop class meant power saws, drill presses, and the occasional unsupervised student figuring things out the hard way. Chemistry class meant open flames and chemicals sitting on benches while the teacher stepped out to handle something else. The assumption in the 1980s was that giving students independence around dangerous equipment built responsibility. Sometimes it did. Sometimes it resulted in the kind of stories people still tell at reunions. Today, any classroom involving hazardous materials or industrial equipment requires a teacher present at all times, and safety protocols cover everything from eye protection to proper chemical storage. Shop class itself has declined significantly in recent decades, partly due to budget cuts and partly due to liability concerns that nobody seemed particularly worried about back then.

Fire Safety

The fire safety situation in many 1980s schools would make a modern building inspector uncomfortable. Exit doors that were locked or blocked, fire extinguishers that hadn't been inspected in years, smoke detectors running on dead batteries - these weren't unusual findings, they were common ones. Fire drills happened occasionally, but the gap between what schools were supposed to maintain and what they actually maintained rarely received serious attention. Today, schools face regular fire safety inspections, mandatory drill schedules, sprinkler system requirements, and strict rules about keeping emergency exits clear and functional. The contrast with the 1980s is significant enough that it's worth pausing on. The buildings felt safe because nothing bad had happened yet, which isn't quite the same thing as actually being safe.

Selling Candy With No Oversight

Before the school vending machine became standard, the entrepreneurial kids in your class had already figured out the market. Backpacks stuffed with candy bars, chips, and homemade baked goods changed hands between classes with no teacher permission, no health department involvement, and no one asking where the food came from or how it had been stored. A popular candy seller could turn a few dollars of weekend shopping into a surprisingly good weekly income. Schools today have strict policies about food sales on campus - nutrition standards, health codes, fundraising approvals, and allergen considerations that make the informal locker-side candy operation completely impossible. At the time it was just a kid with good business instincts and a well-positioned locker. Nobody considered it a problem worth addressing.

Public Reading of Grades

Picture this: the teacher walks back into class with a stack of graded tests, calls out your name, and announces your score to everyone in the room. That was a routine experience in many 1980s classrooms, delivered under the theory that public accountability would motivate students to do better next time. For students who scored well, it was a moment of quiet pride. For everyone else, it was something else entirely. The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, known as FERPA, now prohibits teachers from disclosing student grades publicly in any form - including reading scores aloud, posting them on a bulletin board, or returning papers in ways that expose one student's results to others. The law existed in the 1980s too. It just wasn't always treated as though it applied.

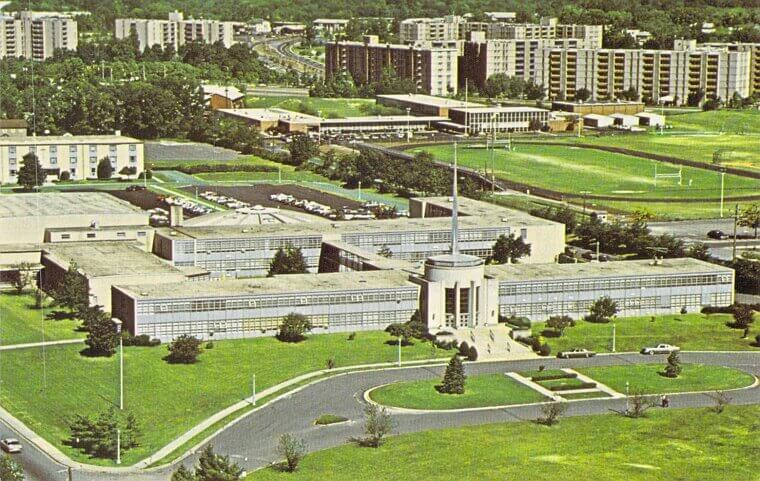

Lack of Amenities for Disabled Students

If you had a disability in the 1980s and wanted to attend a regular public school, the building itself was often the first obstacle. Most schools were designed entirely around able-bodied students - no ramps, no accessible bathrooms, no accommodations for students who needed them. The Education for All Handicapped Children Act had passed in 1975, but funding was inconsistent and implementation was slow throughout the early 1980s. Many students with disabilities were educated at home or in separate facilities simply because the neighborhood school wasn't equipped to include them. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act strengthened protections significantly in the years that followed. Today, schools are required to provide appropriate education to students with disabilities in the least restrictive environment possible - a standard that would have been unrecognizable to most schools just four decades ago.

Driving to School at Fifteen

In many parts of the country in the 1980s, getting your learner's permit felt like the starting gun for a new era of independence - and some teenagers didn't wait long to test it. Depending on the state, a fifteen-year-old with a learner's permit could legally drive to school alone, or close enough to alone that nobody was checking too carefully. Parking lots at some high schools held cars driven there by kids who weren't old enough to vote, buy a lottery ticket, or see an R-rated movie without a parent. Graduated licensing laws, which phase in driving privileges gradually based on age and experience, didn't become widespread until the late 1990s and 2000s. Before that, the rules varied enough from state to state that a fifteen-year-old behind the wheel was, in many places, perfectly legal.