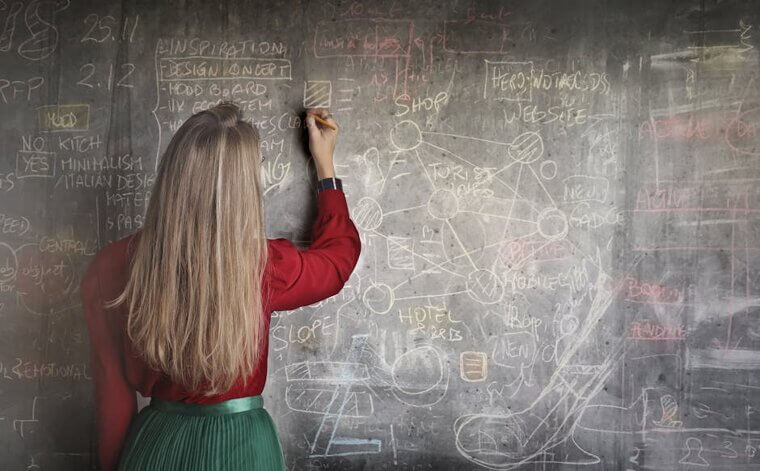

Chalkboards and Dusty Erasers

The chalkboard was the center of every classroom, and the teacher's relationship with it said a lot about how the day was going to go. Write too lightly and nobody in the back could see a thing. Press too hard and you got that screech that made thirty kids wince at the same moment. The chalk itself was unpredictable - snap it wrong and the piece went flying. Erasers collected chalk dust the way old furniture collects everything, and cleaning them meant taking them outside to clap together, which sent a white cloud into the air and accomplished mostly nothing. Some teachers had students do this as a reward, which tells you something about how limited the reward options were. By the end of the day, the board was a palimpsest of half-erased notes, and the chalk rail was covered in dust that ended up on every sleeve that touched it.

Handwritten Homework on Loose-Leaf Paper

Every assignment began the same way. You tore a sheet carefully from your three-ring binder, trying to avoid the ragged fringe that happened when you went too fast. Then came the header: your name in the top right corner, the date below it, the subject below that, all in your best handwriting because first impressions mattered even on a page nobody but the teacher would ever see. If you made a mistake, you crossed it out or started over. There was no backspace, no undo, no quietly fixing something after the fact. Messy papers got marked down, which meant handwriting itself was a skill that carried real academic weight. You developed your own system for correcting errors neatly - a single line through the mistake, never a scribble - and by the end of the school year your notebook was a complete handwritten record of everything you'd learned.

Card Catalogs in the Library

The card catalog was a massive wooden cabinet that took up a significant portion of the library, filled with dozens of narrow drawers each holding hundreds of small index cards in alphabetical order. Finding a book meant pulling open one of those drawers - always stiffer than you expected - and flipping through the cards until you found the right title or subject. Then you copied the call number onto a scrap of paper and went hunting through the stacks. If someone had checked the book out already, that was that. You came back tomorrow and tried again. Librarians knew that catalog better than anyone knew anything, and asking for help meant watching someone navigate it with the easy confidence of long practice. The whole system required patience, a decent memory, and the ability to read someone else's handwriting on a three-by-five card.

Teachers Taking Attendance by Calling Names

First thing every morning, the teacher picked up a clipboard and went through the class list name by name. You raised your hand and said "here," which confirmed you were physically present and paying enough attention to respond. The whole process took several minutes, and the rhythm of it was the same every day - last name first, first name second, a pause while you answered, then on to the next. There was always one name that caused a small delay, either because it was long, unfamiliar, or had a pronunciation the teacher hadn't quite settled on. The student with that name had usually stopped correcting anyone by October. Everyone else had heard it mispronounced enough times that the wrong version started to sound right. No scanner, no app, no automated system - just a teacher, a list, and the same reliable roll call every single morning.

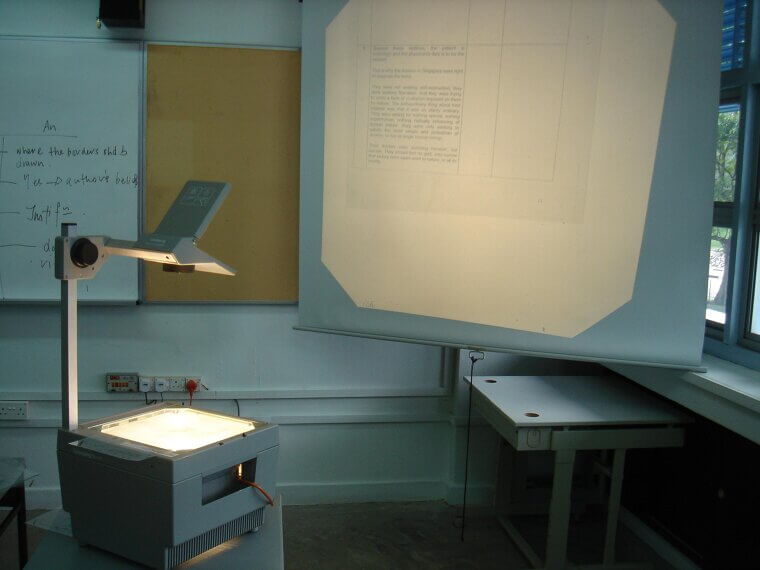

Overhead Projectors With Transparent Sheets

You knew class was about to get serious when the teacher wheeled out the overhead projector. The bulb clicked on, light blasted up through a transparent acetate sheet, and your notes appeared on the wall in slightly crooked, slightly blurry glory. Teachers wrote directly onto the sheets with special markers while talking, which meant their handwriting was either perfectly legible or completely illegible depending on how fast they were moving. The real trick came when they layered multiple sheets on top of each other to build a diagram step by step - adding a label here, an arrow there, peeling one back to reveal another. It felt surprisingly dramatic for a piece of office equipment. Every classroom had one, every teacher used one differently, and the faint hum of that cooling fan became the background sound of an entire era of learning.

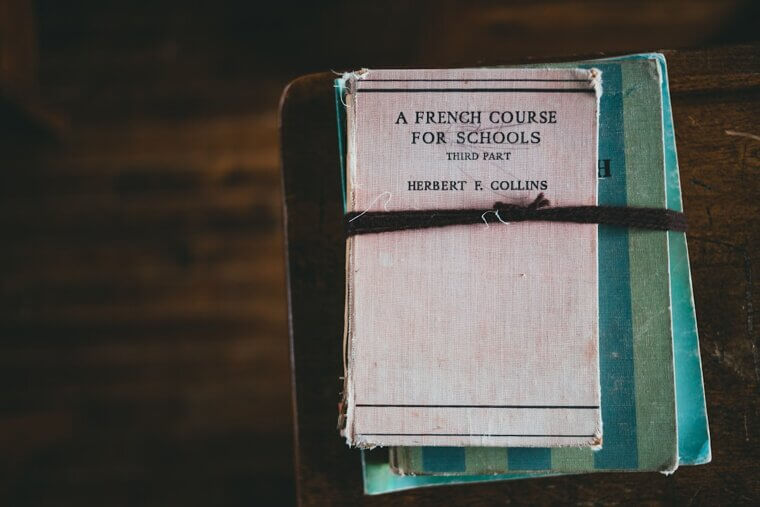

Textbooks That Weighed More Than Your Backpack

Every subject came with its own hardcover textbook, and the expectation was that you brought all of them to school every day. By middle school that backpack weighed enough to cause real discomfort on a long walk. The books themselves were built to last - thick covers, heavy paper, hundreds of pages covering a subject in more depth than most courses ever actually reached. They also had a way of being slightly out of date by the time they reached you, passed down through several years of students who'd left their own marks in the margins. You could tell a lot about previous owners from the underlining and the doodles in the chapter headers. Some books smelled like every classroom they'd ever been in. When a new edition arrived, the old ones didn't disappear - they just got used for another decade.

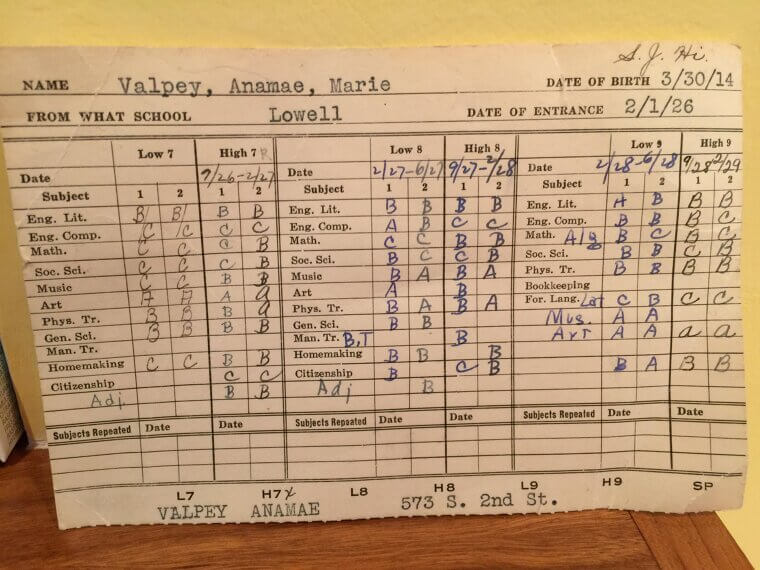

Hand-Written Report Cards and Grade Books

Your teacher kept a grade book - a physical ledger, usually with a dark cover and graph paper inside - where every quiz score, test result, and homework grade was recorded by hand in ink. At the end of each grading period, they sat down with that book and calculated averages using actual arithmetic. No spreadsheet, no algorithm, no automatic update the moment a grade was entered. Report cards were filled out the same way, each comment written individually for each student. When you brought yours home, the handwriting told you something about your teacher's state of mind - careful and deliberate, or rushed at the end of a long grading week. Parents signed them and sent them back. Everything about the process was manual, personal, and slightly anxiety-inducing in a way that a number appearing on a portal at midnight somehow isn't.

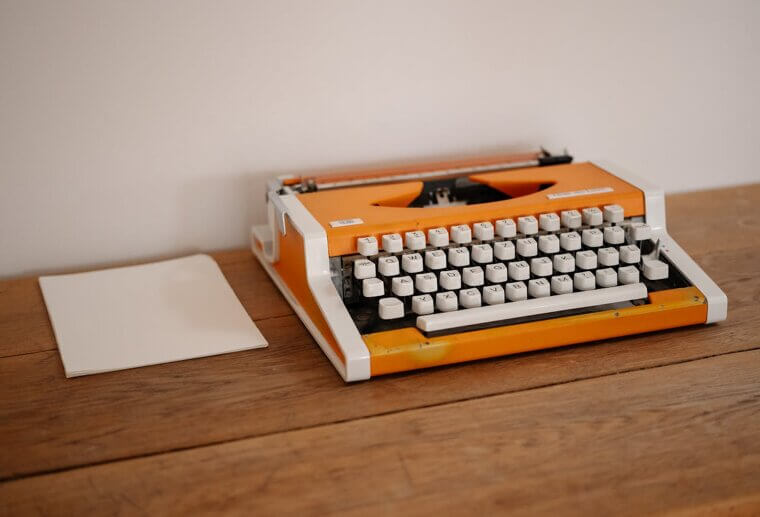

Typewriters for Assignments and Final Papers

Typed assignments carried a certain authority that handwritten ones didn't, which meant getting access to a typewriter mattered. The family typewriter, if there was one, was loud and mechanical and completely unforgiving. Every keystroke was permanent. A mistake meant reaching for the bottle of white correction fluid, waiting for it to dry, and typing over it while hoping the alignment held. There was no spell-check catching errors before you committed to them, no way to move a sentence once you'd typed it in the wrong place, and no quiet revision after the fact. School computer labs sometimes had early word processors that handled some of this better, but they were shared, limited, and required signing up in advance. A perfectly typed final paper felt like a genuine accomplishment because every clean page represented real effort to get it right the first time.

Pull-Down Maps and Classroom Globes

Every classroom had a pull-down map mounted above the chalkboard, rolled up like a window shade and released with a satisfying snap when the teacher yanked the cord. The globe sat on a shelf or the corner of the desk, and spinning it felt almost philosophical - all that geography turning under your finger. Maps got outdated faster than anyone updated them, so borders in certain parts of the world didn't always match current events, which occasionally made for interesting classroom discussions. Political geography moved faster than school budgets. The globe was more reliable for physical features - mountain ranges, ocean basins, the basic shape of continents - and students who studied it closely developed an intuitive sense of where things were in relation to each other that no digital map has quite replaced.

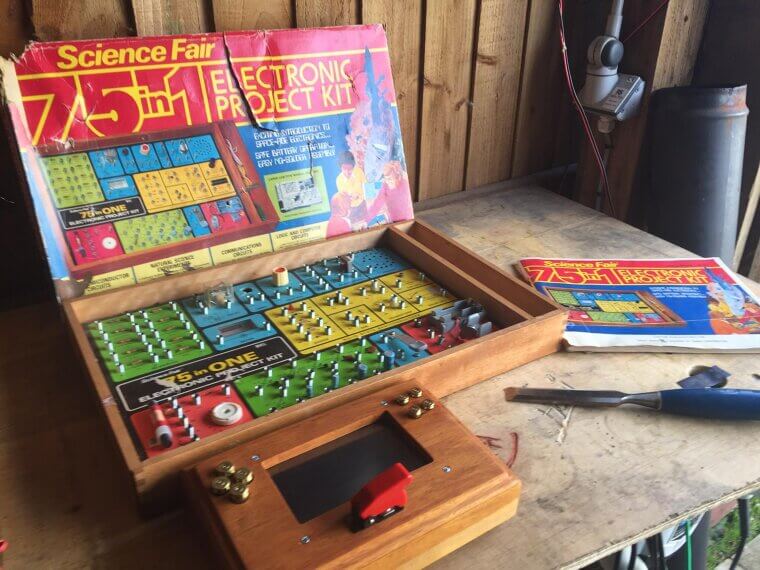

The Project Display Boards for Science Fairs

The science fair display board was a rite of passage. You bought it at the drugstore - white, black, or sometimes a color if you were feeling ambitious - and spent an entire weekend turning it into something presentable. The text got typed or carefully hand-lettered. The charts were drawn by hand with rulers and colored pencils. Photos got cut and glued in straight lines that never quite stayed straight. The whole thing had to stand on its own, which it did until someone walked past it too quickly. Teachers judged them with clipboards and serious expressions, asking questions about methodology that you'd rehearsed the answers to the night before. The best ones had working models - a volcano, a circuit board, something that actually did something. Yours probably had a hypothesis and a conclusion and a photograph of you doing the experiment in the kitchen.

Paper Planners and Assignment Diaries

Every student got a planner at the start of the school year - a small spiral-bound book with a week laid out on each page and boxes for each day where you were supposed to write down homework, test dates, and project deadlines. The system worked if you used it consistently, which most students did for about two weeks before life intervened. By November the planner had been forgotten somewhere at the bottom of a locker, and the organizational system had quietly collapsed back into trying to remember things. Finding it again weeks later was its own small archaeology project - a record of the last time you'd felt on top of things, with homework assignments in ballpoint pen that were either long finished or long overdue. Teachers checked them sometimes, which created a brief revival of use that faded just as quickly.

Running to the Library Before Someone Else Got the Good Books

When a research project got assigned, the library became a competitive environment almost immediately. The teacher announced the topic, and every student in the class understood simultaneously that there were maybe four decent books on the subject and twenty-five people who needed them. The card catalog was the first bottleneck - everyone converging on the same drawer at once, flipping through the same index cards looking for the same call numbers. Then came the stacks, where being fast mattered. The student who arrived first got the complete, well-illustrated copy. The one who arrived second got the older edition. The ones who arrived last got the book with the water-damaged cover and several pages missing, which they used anyway because it was what was left. You learned quickly that library research rewarded preparation, and that showing up a day early to check what was available changed everything.

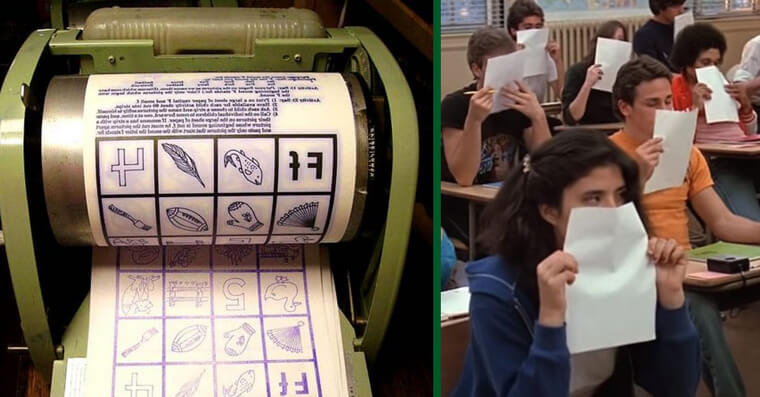

Mimeograph Handouts

There was a smell that meant the teacher had spent time at the mimeograph machine before class, and you knew it the moment the stack of papers started moving down the row. Sharp, chemical, faintly sweet - the scent of freshly printed purple or blue ink that hadn't fully dried yet. You held the paper and could feel that it was slightly damp. The ink smudged if you ran your finger across it wrong. Every student in the class knew that smell, and for a generation of people who went to school in the 1970s and 1980s, it's one of those sensory memories that comes back completely intact when something similar triggers it. The mimeograph gave way to the photocopier, which was cleaner and sharper and produced black ink that didn't smudge. Something was lost in that transition, though nobody could quite explain what.

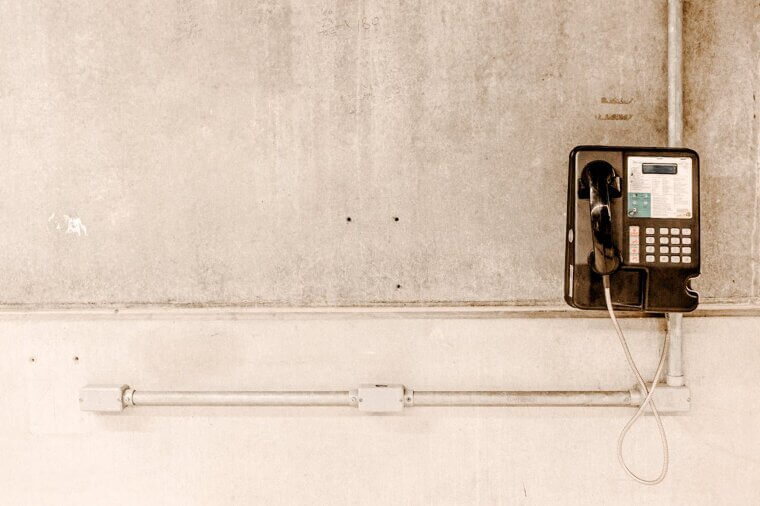

Classroom Phone Only for Emergencies

There was a phone on the wall near the teacher's desk, and it was not for student use under any ordinary circumstances. It rang occasionally during class - a sound that immediately shifted everyone's attention - and the teacher would answer it, listen, say something brief, and hang up. Sometimes it meant a student was being called to the office. Sometimes it was a message from the front desk. Whatever it was, it came through that single phone on the wall, because that was the only way information moved into a classroom from outside it. Students who needed to reach a parent went to the office and used the phone there, which required a documented reason and felt like a formal process. The idea that every student would one day carry a personal communication device in their pocket would have seemed like something out of a science fiction story.