Rotary Dial Telephones

If your family had a rotary phone - and in the 1960s and 70s, nearly every family did - you already know that making a call required a level of patience that modern phones have made completely unnecessary. You put your finger in the hole for each digit, pulled the dial around to the metal stop, and waited for it to spin back before starting the next one. A long number like a friend across town meant a good ten seconds of dialing before you even heard a ring. Mistakes meant hanging up and starting over. The phone sat in one place - the kitchen counter, the hallway table, the bedroom nightstand - and the cord only reached so far. Talking on the phone meant staying in one spot for the entire conversation. That was just how it worked, and nobody questioned it.

Film Cameras

Every family had a camera for the important moments, and every camera required film. You loaded the cartridge carefully, advanced it to the first frame, and then used each shot deliberately because there were only 24 or 36 of them and developing the roll cost money. Blurry, overexposed, or badly framed photos were only discovered later, when you picked up the envelope at the drugstore and flipped through the prints. No deleting, no retaking, no checking the screen immediately after. What you got was what you got. The good ones went into albums. The others went into a box. Film cameras stayed in service even as technology moved past them because they worked reliably and the pictures they produced had a quality that digital images have spent decades trying to replicate. Many of those old prints, faded to warm tones now, are still the best photos some families have.

Transistor Radios

The transistor radio made something possible that hadn't been possible before: you could take the radio with you. Small enough to fit in a shirt pocket, running on a couple of AA batteries, picking up AM stations from surprising distances - the transistor radio was a genuine piece of freedom for anyone who wanted news or music away from the house. You took it to the backyard, to the beach, to a baseball game, anywhere you went. Reception faded in and out depending on where you were standing and which direction you held it, which meant there was a particular pose - arm up, radio tilted slightly - that every owner recognized as the position that got the best signal. The sound wasn't rich, but it was there. For a generation that grew up without portable anything, having music in your pocket felt remarkable.

The Milkman

Milk arrived at the doorstep in glass bottles, left by the milkman in the early morning before most households were awake. You put the empty bottles out the night before, left a note if your order was changing that week, and came down in the morning to find cold bottles waiting on the step. The milkman knew his route the way a neighbor knows a neighborhood - which houses took two quarts, which ones had added cream, which family had just had a baby and would need extra. It was a system that worked reliably for decades, built on consistency and quiet routine. Supermarkets and home refrigeration made it economically impractical, and the deliveries stopped. The glass bottles gave way to cardboard cartons, then plastic jugs. The milk is the same. The experience of finding it waiting on your doorstep on a cold morning is something that generation remembered their whole lives.

Party Line Telephones

Before private phone lines were standard, many households shared a party line with their neighbors - a single telephone line connecting multiple homes on the same street or block. You picked up the phone and might find your neighbor already mid-conversation. The polite thing was to hang up quietly and try again later. The less polite thing, which plenty of people did, was to stay on the line and listen. Privacy on the telephone was something you hoped for rather than something you counted on. Operators sometimes managed the lines and could hear calls too. Getting your own private line eventually felt like a genuine upgrade in how you lived, a small but meaningful shift toward the idea that a conversation between two people was actually between two people. Party lines disappeared gradually as telephone infrastructure expanded, and very few people missed them.

8-Track Tapes

Taking your music with you in the car meant something very specific in the 1960s and 70s - it meant 8-track tapes. The cartridge was chunky and solid, slid into the player with a satisfying click, and filled the car with whatever you'd loaded before you left the driveway. You couldn't skip tracks, couldn't rewind, couldn't do much of anything except listen in order and hope your favorite song wasn't the one that got cut in half when the tape switched programs. That happened regularly, right at the worst possible moment, and there was nothing to be done about it. The tapes wore out eventually, getting slower and muddier until they gave up entirely. Cassettes replaced them, then CDs replaced cassettes, then everything moved to a phone. But for a specific stretch of years, the 8-track was how music traveled with you.

Console Televisions

The television set in a 1960s or 70s living room wasn't just an appliance - it was a piece of furniture. Console televisions came housed in large wooden cabinets designed to sit alongside the sofa and the bookshelf and look like they belonged there. The cabinet had doors you could close when the TV wasn't in use, which made the whole thing look more like an armoire than an entertainment device. Changing the channel meant getting up and turning a dial, and the number of channels available in most homes could be counted on one hand. The picture was good enough, the color arrived gradually through the decade, and the whole family sat in the same room and watched the same thing. Flat screens eventually reduced the television to a thin panel on the wall. Something about the furniture version felt more considered, more permanent, more like it had earned its place in the room.

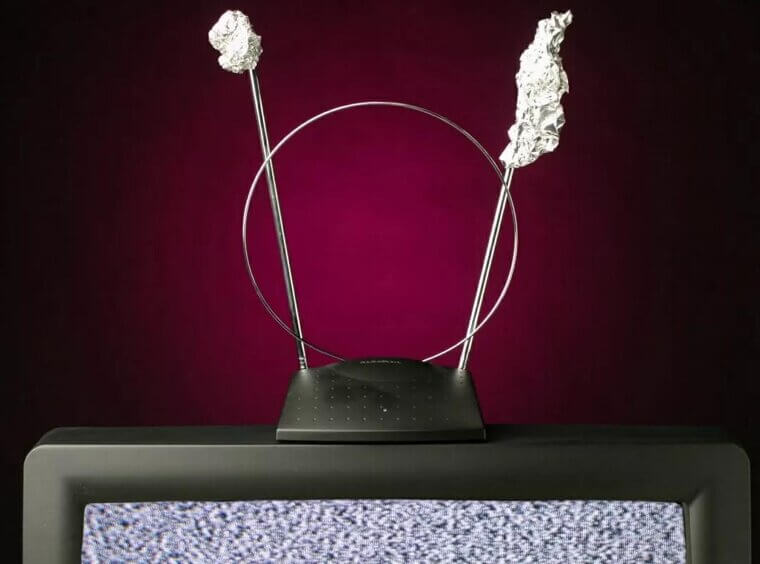

Rabbit Ear Antennas

Getting a clear picture on a 1960s or 70s television required negotiation. The rabbit ears - two telescoping metal rods extending from the top of the set - picked up broadcast signals, and the quality of what you saw depended entirely on how you positioned them. You'd spread them apart, angle them toward the window, wrap a piece of aluminum foil around one of them, stand in a specific spot in the room. Sometimes moving two inches to the left made the difference between a clear picture and a screen full of static. When you found the position that worked, you left everything exactly as it was and told everyone else not to touch it. Cable television eventually made rabbit ears unnecessary for most households, and the relief was genuine. Getting a clear picture without adjusting anything first felt like a small luxury that people who grew up with antennas genuinely appreciated.

Drive-In Movie Theaters

A Friday night at the drive-in was its own kind of experience, different from anything a movie theater inside a building could offer. You drove in, found a spot, hung the speaker on your window, and watched the movie from your car with whatever food you'd brought from home or picked up at the snack bar. Kids in pajamas fell asleep in the back seat. If the movie was good, you stayed for the second feature. If it wasn't, you talked through it anyway and still had a fine evening. Drive-ins required a lot of land, and as land values rose through the 1970s and 1980s, the economics stopped working. Most closed. A few survived and a handful have opened again in recent years, which tells you something about how much people missed the experience. Watching a movie outdoors from your own car turned out to be harder to replace than anyone expected.

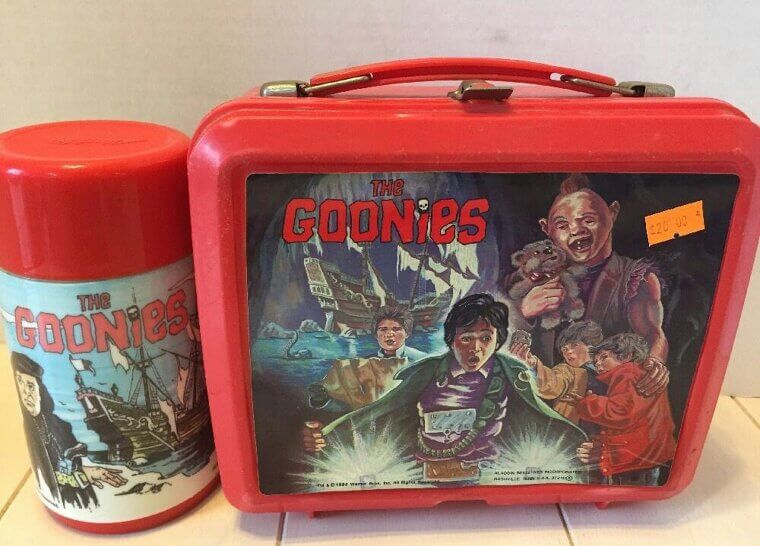

Metal Lunchboxes

A metal lunchbox was more than a container for your sandwich - it was a statement about who you were at seven years old. The lid had a scene from a TV show or a cartoon pressed into the metal in full color, and the matching thermos inside kept whatever was in it at the right temperature until lunchtime. You carried it by the handle, it made a distinctive sound when you set it down on a desk, and the latch clicked open with a particular feel that every kid who owned one remembers. The contents mattered too - what your mother packed said something about your house and your family that you were just old enough to be aware of. Plastic eventually replaced metal, and soft insulated bags replaced both. The old lunchboxes became collectibles, which makes sense. They were small and ordinary and somehow ended up meaning more than they were ever supposed to.

Wood-Panel Station Wagons

The family station wagon with wood paneling along the sides was as much a symbol of American suburban life in the 1960s and 70s as the ranch house and the backyard barbecue. It held the whole family, the luggage, the dog, and whatever else needed to come along, and it did all of it without pretending to be anything other than practical. The faux wood paneling wasn't real wood, but it gave the car a warmth that plain metal sides didn't have, and it became the identifying feature of an entire era of family transportation. Road trips happened in station wagons. Vacations started in the driveway with everyone piling in. The minivan replaced it in the 1980s, and the SUV replaced the minivan, and somehow none of the replacements have quite the same character. People who grew up riding in the back of a station wagon tend to remember it fondly.

Lawn Darts

Lawn darts - sold under the brand name Jarts among others - were exactly what they sound like: heavy metal darts, weighted at the front, designed to be thrown high in the air toward a plastic ring on the ground. The game was genuinely fun, and it was genuinely dangerous, and for most of the 1960s and 70s those two things coexisted without anyone in the toy industry considering it a problem worth solving. Families played with them at cookouts and on summer afternoons without incident, mostly, and when incidents did occur they were serious enough that the Consumer Product Safety Commission eventually banned them entirely in 1988. The ban covered all versions with metal tips. If you still have a set in the garage from those years, they're technically illegal to sell. For people who grew up playing with them, they represent a particular era when childhood came with considerably more risk built in.

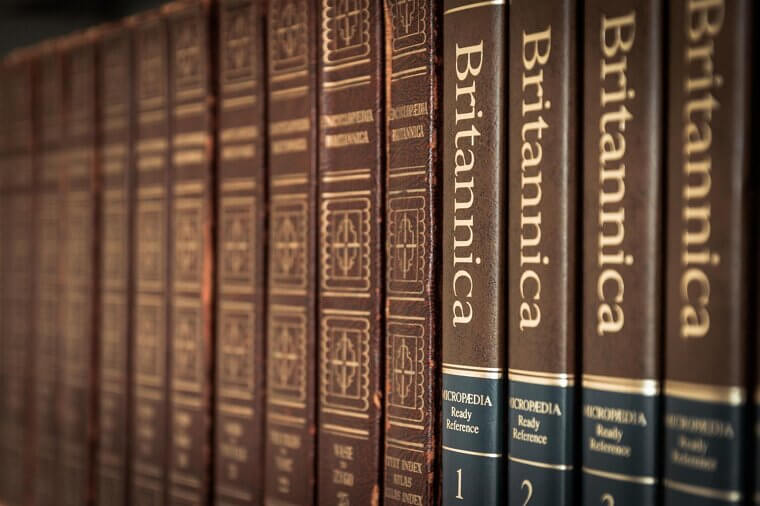

Encyclopedias

A set of encyclopedias on the bookshelf meant something in the 1960s and 70s - it meant the family had invested in knowledge, had made room for it, had decided it mattered enough to spend real money on. The volumes arrived from a door-to-door salesman, one at a time over months of payments, and were arranged on a dedicated shelf where they stayed for decades. When a school project came up, you went to the shelf and found the right volume and read what it said, even when what it said was a few years out of date. The writing was dense and authoritative and covered everything from aardvarks to Zoroastrianism with the same confident tone. Wikipedia replaced encyclopedias completely and did it quickly, but something about having the physical books - the weight of them, the smell of the pages - made looking something up feel like it mattered.

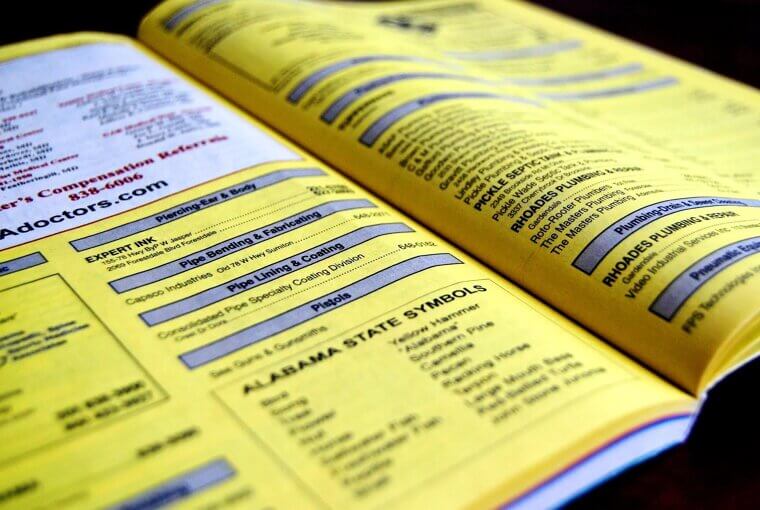

The Yellow Pages

The Yellow Pages arrived once a year, dropped on the doorstep without being ordered, and immediately became one of the most consulted books in the house. Every local business that wanted to be found paid to be listed, organized by category, with the bigger advertisers getting larger boxes and bolder type. Looking up a plumber meant flipping to P, scanning the listings, and calling whoever seemed most established or had the most prominent ad. There was no way to read reviews, no way to check ratings, no way to know much beyond the name and the phone number and whatever the business had chosen to say about itself. You made your best guess and called. The internet made the Yellow Pages obsolete almost overnight, and the last printed editions felt like artifacts before they'd even stopped being delivered. For thirty years they were indispensable. Then, quite suddenly, they weren't.

Metal Ice Cube Trays

The metal ice cube tray with the lever handle was a small domestic technology that worked through pure mechanical cleverness. You filled the tray with water, set it in the freezer, waited, and then when you needed ice you grabbed the lever and pulled it toward you. The lever twisted the metal grid just enough to crack each cube free from the tray all at once, and they fell into whatever you were holding underneath. It required a certain technique - too gentle and nothing happened, too hard and half the cubes shot across the counter. The metal got very cold and stuck to warm fingers in winter. Plastic trays came along and were easier to manufacture, then automatic ice makers arrived and removed the process entirely. The metal tray with its lever disappeared from most kitchens without anyone making much fuss about it, which is how most useful things go.