Growing up on Home Cooked Dinners in the 60s and 70s

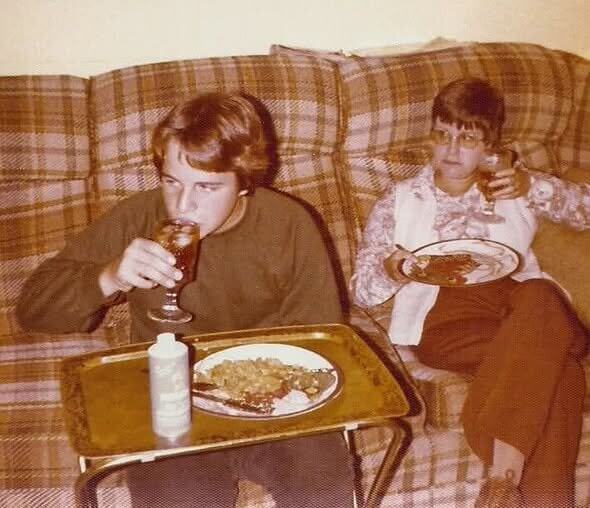

If you grew up in the 60s or 70s, dinner was usually homemade and happened at a predictable time. Meals were cooked from scratch, often with the same familiar dishes rotating week after week. There was meat, a starch, and at least one vegetable, whether kids liked it or not. Portions were reasonable, seconds were earned, and snacking between meals was limited. This kind of structure quietly taught balance without lectures or rules written down. Kids learned to eat what was served and stop when full because dessert was not guaranteed. As adults, many carried forward that sense of moderation. Eating felt normal rather than emotional. That steady relationship with food often supports long term consistency, which tends to matter more than any single ingredient or trend.

Meat and Potatoes as the Backbone of Every Meal

For many families in the 60s and 70s, dinner meant meat and potatoes, plain, filling, and dependable. It was not flashy food, but it showed up night after night with quiet reliability. A roast, chops, meatloaf, or fried chicken usually took center stage, with potatoes baked, mashed, or fried alongside a simple vegetable. Meals rarely experimented beyond what the family already knew and trusted. This kind of upbringing often created a straightforward relationship with food. Eating was about nourishment and routine, not trends or novelty. People raised this way tend to carry that steadiness into adulthood. They often prefer familiar meals and predictable schedules, finding comfort in consistency rather than variety for variety’s sake. That predictability can be grounding over a lifetime. Food does not feel emotional or complicated. It is practical, filling, and reliable. Over decades, that calm, no drama approach to eating often supports habits that last simply because they feel normal and sustainable.

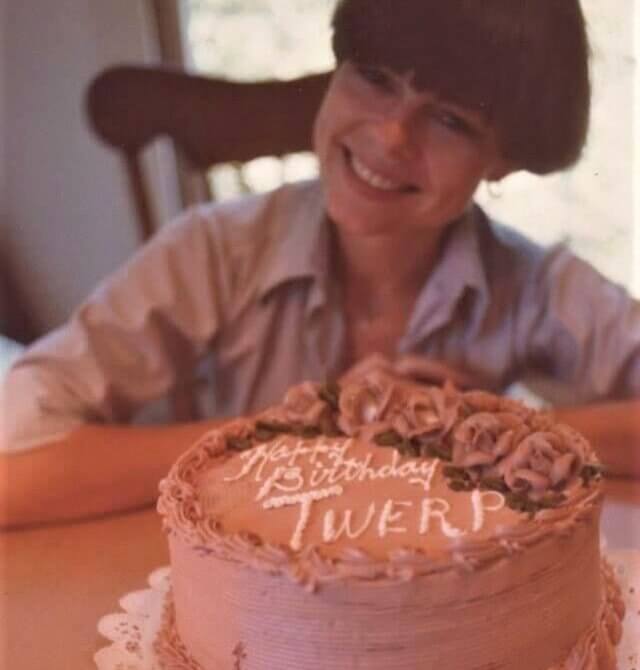

Desserts That Were Regular but Not Endless

In many 60s and 70s households, desserts were common but controlled. Cookies, cakes, pies, and puddings appeared regularly, but they were usually homemade and served in modest portions. Dessert was something to look forward to, not something that dominated the day. Kids learned quickly that sweets were part of life, but not unlimited. You had dessert after dinner, not whenever you felt like it. This created a surprisingly relaxed relationship with treats. Because nothing was forbidden, desserts did not feel powerful or obsessive. As adults, many people raised this way continue to enjoy sweets without guilt or urgency. They are comfortable having dessert and equally comfortable skipping it. That balance often sticks for decades. Desserts remain enjoyable rather than emotional, which quietly supports steadier habits over time.

Seasonal Eating Without Calling It That

In the 60s and 70s, most families ate with the seasons without ever using the phrase seasonal eating. Certain foods simply appeared at certain times of year. Fresh tomatoes showed up in summer, apples in fall, and heavier meals in winter. Families adjusted naturally, shopping for what was available and affordable. This way of eating taught patience without trying to. You waited for strawberries, corn, or peaches because that was how it worked. People raised this way often develop a comfort with variety and timing later in life. They are less bothered by waiting and less driven by constant availability. That mindset tends to carry forward quietly, shaping long term habits that feel flexible and intuitive rather than forced.

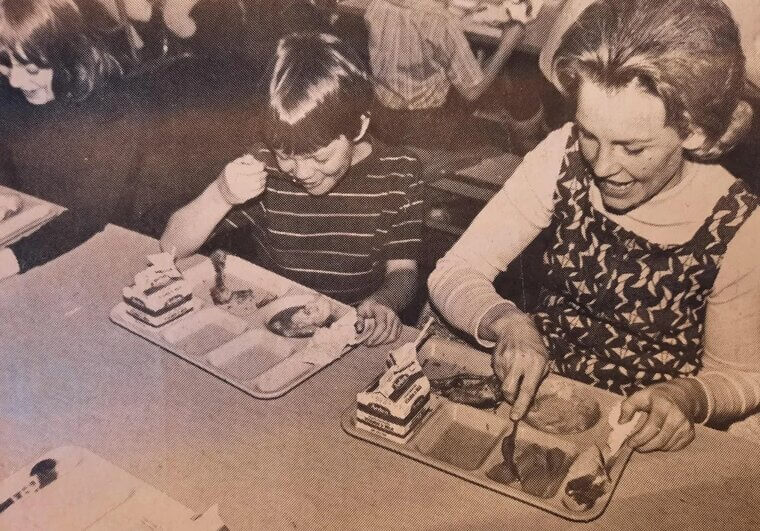

School Lunches and Packed Snacks

School lunches and packed snacks were a daily reality for many kids in the 60s and 70s. Cafeteria trays offered limited choices, and packed lunches reflected whatever was at home. Kids learned quickly how to manage what they had. They traded items, saved favorites for last, and paced themselves through meals. This early exposure to choice within limits taught practical decision making around food. As adults, people raised this way often approach eating without anxiety. They are comfortable making selections, adjusting portions, and moving on. Food does not feel overwhelming. That calm relationship with choice often supports steadier habits across life, simply because eating never became a source of stress.

Strict Food Rules at the Table

Food rules were common in the 60s and 70s. Finish your plate. No snacks before dinner. Eat what is served. These rules were rarely explained, but they were enforced consistently. For some kids, the rules felt rigid. For others, they created structure. Either way, they made people aware of food and mealtime boundaries. As adults, many people softened those rules, but the awareness often remained. Eating rarely felt chaotic. There was a sense of timing and order. That structure can evolve into mindfulness later in life when it loosens with experience. Awareness without rigidity often becomes balance over time.

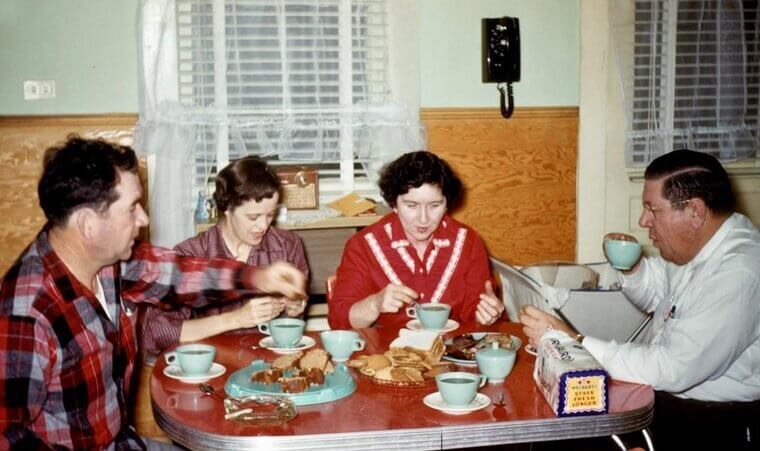

Big Family Meals and Long Dinners

Family meals in the 60s and 70s were rarely rushed. Dinner was a shared event, not something squeezed between activities. Conversations unfolded slowly, and meals often lasted longer than planned. Kids learned to sit, wait, and listen as much as they learned to eat. That pacing often stays with people for life. Adults raised this way tend to eat more slowly and view meals as social experiences rather than tasks. Slowing down naturally supports steadier habits because it removes urgency from eating. Food becomes part of connection, not something to rush through.

TV Dinners and Fast Food Nights Becoming Normal

By the late 60s and into the 70s, TV dinners and drive thru meals started showing up more often. Aluminum trays slid into ovens, and dinner sometimes happened in front of the television. Kids raised this way learned flexibility early. Meals did not always look the same, and eating schedules shifted. As adults, many from this background became adaptable eaters. They are comfortable eating out, adjusting routines, and trying new things without stress. While convenience foods were part of childhood, so was learning how to roll with change. That adaptability often carries into later life in ways that help people adjust as needs and habits evolve.

Simple, Repetitive Breakfasts

Breakfast in the 60s and 70s rarely changed. Cereal, toast, eggs, or oatmeal showed up again and again. That repetition created a stable start to the day. Kids knew what to expect, which reduced decision making early in the morning. As adults, many people raised this way appreciate simple routines. They are comfortable eating the same breakfast for years. That consistency often becomes a quiet anchor in daily life, supporting long term routines that feel grounding rather than restrictive.

Food as Comfort, Not Calculation

In the 60s and 70s, food comfort was emotional but uncomplicated. Soup appeared when someone was sick. Cake marked birthdays. Certain dishes meant home and safety. There was no counting or analyzing. Food comfort was about care, not control. People raised with that mindset often carry it forward in healthy ways. Food remains tied to memory and connection rather than stress. When comfort stays rooted in tradition and moderation, it often supports satisfaction and steadiness over a lifetime.